Wednesday, June 28, 2006

Saturday, June 10, 2006

Tuesday 3/7/06 Day Three

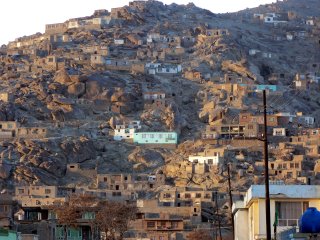

Above and below 3 pics:Around Kabul (taken by Cordelia Persen)

Above and below 3 pics:Around Kabul (taken by Cordelia Persen)

Below pic: International Center for Human Rights and Democratic Development event celebrating women who taught privately in their homes during Taliban

Below pic: International Center for Human Rights and Democratic Development event celebrating women who taught privately in their homes during Taliban

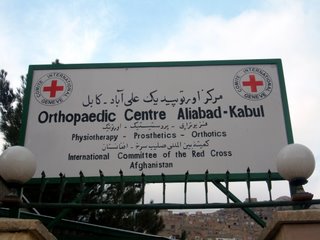

Below 9 pics: A visit with the ICRC/International Center of the Red Cross

Below 9 pics: A visit with the ICRC/International Center of the Red Cross

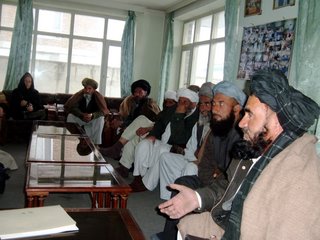

Below 4 pics: A visit with the Afghanistan Commission for Human Rights (where we had the honor of speaking with a group of men from Ghazni)

Below 4 pics: A visit with the Afghanistan Commission for Human Rights (where we had the honor of speaking with a group of men from Ghazni)

Our first visit this day was in response to a spontaneous invitation to an event held by Rights and Democracy: International Center for Human Rights and Democracy (a Canadian/Afghan organization - http://www.wraf.ca/ .) It was a ceremony celebrating women who risked imprisonment by holding classrooms secretly in their homes during the Taliban regime. We sat at the back of a fairly large auditorium and stayed for the first twenty minutes or so - the fact that the ceremony was (naturally) held in Dari made the novelty wear out quickly. But it was nice to show support. We attracted a lot of attention from young women sitting within our vicinity who eagerly whispered conversation with us in order to practice their English skills. Media covered the event, and later that evening, we even had a chance to see ourselves on the Kabul local news as the camera spanned the audience during the story coverage......On the brochure for the event was a quote I especially like by Martin Luther King, "Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about the things that matter."

Our first visit this day was in response to a spontaneous invitation to an event held by Rights and Democracy: International Center for Human Rights and Democracy (a Canadian/Afghan organization - http://www.wraf.ca/ .) It was a ceremony celebrating women who risked imprisonment by holding classrooms secretly in their homes during the Taliban regime. We sat at the back of a fairly large auditorium and stayed for the first twenty minutes or so - the fact that the ceremony was (naturally) held in Dari made the novelty wear out quickly. But it was nice to show support. We attracted a lot of attention from young women sitting within our vicinity who eagerly whispered conversation with us in order to practice their English skills. Media covered the event, and later that evening, we even had a chance to see ourselves on the Kabul local news as the camera spanned the audience during the story coverage......On the brochure for the event was a quote I especially like by Martin Luther King, "Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about the things that matter." Our next destination was the ICRC/International Center for the Red Cross Orthopedic Project. This, I must say, was one of the more intense visits of the trip (of many), which succeeded at bringing tears to my eyes. This particular center started in 1988 and has since grown to a total of six centers in Kabul and five other provinces. The project was originally intended for war wounded disabled only, but from 1995 the assistance has been extended to any kind of motor disabled, whether war wounded or non-war wounded. The project's five main activities are: Production of leg and arm prostheses; production of orthoses (splints, braces, wheelchairs, etc.); physical rehabilitation; training of local staff (in which only disabled are employed*); and social re-integration of the disabled (employment, micro-credit, education, vocational training, apprenticeship.)

* The main physical therapist that spoke with us and showed us around light-heartedly joked that some people call them discriminatory for hiring only disabled, but that the center frankly didn't care to be accused of such.

All services provided by the center are free. This particular center serves between 200 - 250 patients a day. In the past eighteen years, the ICRC has served 75,000 patients around the entire country, 38,000 of them in Kabul. 80% of amputations are due to land mine accidents.

The physical therapist we spoke with himself lost both his legs in a land mine accident at age eighteen. He came to the ICRC initially as a patient, was eventually asked to work in the center, then pursued schooling for physical therapy, and has dedicated his life to working for the ICRC ever since. He was certainly a very inspiring man.

We had a chance to tour the facility, which was interesting to me until we arrived at the rehabilitation rooms. Watching people, young and old, struggle to make seemingly painful attempts at walking just seemed too voyeuristic to me. This was the moment that I was sincerely moved to tears as I had to duck out in order to compose myself.

The final visit of the day was with the Office of Afghanistan Commission for Human Rights (ACHR - which offers legal advice, information, and aid) and one of the representatives, Mr. Lal Gul. As we approached the home where the organization was located, a group of approximately ten men wrapped in wool shawls and donned in elaborate head-wraps were getting up to leave the informal conference room. Someone in our delegation joked that we request that this group of intriguing men stay in order to converse with them. Najib, always eager to accommodate, giggled in response to the request, whimsically joined his hands together, replied "Building people-to-people ties..." (Global Exchange's motto), and went inside to inquire if the group would be willing to meet with us. The men agreed, additional chairs were brought into the room, and our delegation filled the remaining half of the room quite snugly. A few people from the organization scurried to bring tea and pastries, which were passed around within a short time. In the meantime, Najib introduced us all to Mr. Gol and the men who agreed to stay, also explaining a bit about Global Exchange and the purpose of our delegation. I was able to decipher quite quickly that Najib wasn't speaking Dari at this point, and that the group of men must be Pashto speaking. When Najib was finished, Mr. Gol shared with us, with their permission, the background and situation of the men we were meeting with, also giving the group an opportunity to ask questions. The men were apart of a tribal group from the province of Ghazni (approximately 150 kilometers from Kabul.) They had traveled to Kabul to speak with the organization to make claims against International and American military for mistreatment of people in their village, for unwarranted arrests of twenty-three people in 2003 (four of which are still imprisoned in Guatanamo Prison under accusation of Taliban involvement), and for the ransacking of money and jewelry from their homes. They also had come to speak with the organization about money issues and their village's lack of medical facilities, schools, and clean water. The dialogue with the group of men lasted about twenty minutes and ended with (of course) a request for group photos outside.

After the thankfully short photo session, the group of men departed and our delegation went back inside to speak with Mr. Gol about the organization itself. The organization was established in 1997. At the time, the Taliban were in Afghanistan and there weren't any human rights organizations running at the time. The ACHR attempted to open their office in Kabul but the Taliban prohibited them from doing so. Thus they opened their office in Pakistan and did service for thousands of Afghan refugees in exile there at the time. The organization functioned as a free legal center and provided aid and advocacy for Afghans whose primary issues were regarding mistreatment from the Pakistani government. The ACHR also worked with war-wounded civilians (many of which were wounded during US bombing on Taliban), providing blood donations, food and clothing. In 2002, the organization moved it's office to Kabul, and continue to provide free legal aid, focusing on a wide range of issues such as children's rights, women's rights and prisoner's rights.

Monday 3/6/06 Day Two (Part 2)

Below pics: A visit with Suraya Parleka of the All Afghan Women Union

Below pics: A visit with Suraya Parleka of the All Afghan Women Union

After our visit with PARWAZ, our vans headed back into the center of town toward a high school that was holding an International Women's Day event and where we would be meeting with Marzia Basel, the founder and director of the Afghan Women Judges Association "AWJA." She greeted us outside of the high school and invited us to come inside and enjoy the theatrical play that was about to begin. Big banners donned the school and the auditorium, honoring women and International Women's Day in both English and Dari. In fact, these banners were first of many that I would see all over the city of Kabul. I was pleasantly surprised by the amount of these banners around town, primarily because of the lack of such banners in the places of which I have lived - in the 'progressive' West, where I embarrassingly had never even heard of International Women's Day until discovering the "Women Making Change" Global Exchange delegation online last winter. My delight in and pondering of this irony only continued to increase throughout the week as I would observe just how celebrated International Women's Day is for many Afghans in Kabul.

The twelve of us were led to the two rows toward the back of the small high school auditorium. The audience was full of Afghan women, men and families, many of whom cast curious glances our way. The play began shortly after - the lights dimmed and the curtains opened, presenting to us a woman dressed in black kneeling on the stage with tied ropes hanging off of her body. Though the play was in Dari, I was able to understand a bit in addition to the evident themes of the play. One by one, male characters entered the stage and presented a dialogue. Over time, it became obvious that these men represented her father, her brother, her husband and her sons - some of them stern, some of the sarcastic, all of them accusatory and yelling, "Zan!Zan!" (Woman! Woman!) pulling on the ropes attached to her body and throwing black peices of cloth over her head. All the while, the kneeled woman remained dignified despite her obvious emotional suffering (well acted, I must add.) After the succession of these men, rows of children entered the stage carrying signs in Dari. Unfortunately I wasn't able to decipher much of the meaning of the writing, but it was quite clear that these children symbolized a certain hope for the future in regards to the status and appreciation of women in society. I must admit that I was quite moved and tears welled up in my eyes (but then again, it really doesn't take much for me to become touched emotionally.)

We were beckoned back into the lobby before the end of the play, much to my dismay as I was really beginning to get sucked into the narrative. But Marzia Basel was waiting to speak with us and it was an honor to speak with such a dignified woman as her. Our meeting with her was slightly rushed, however, and as I refer to my journal notes now, three months after returning, I find that only a few sentences were written in regards to our meeting with her. Ms. Basel, who used to work for the United Nations, is the founder and the director of the Afghan Women Judges Association/AWJA.

"Marzia Basel has both extensive training and experience in international relations, women in development, and law. After receiving her Bachelor's in Law and Political Science from Kabul University in 1985, she was employed as a judge in both civil and criminal courts in Kabul and later served in The Supreme Court Legal Aid Department and the Kabul Public Security Court. During the years of 1996-2001 in which the Taliban ruled Afghanistan, Basel ran a private, home-based school for women where she designed programming and taught English. Since the fall of the Taliban, she has been very active in state reconstruction serving on the Kabul Public Security Court , acting as a representative for the establishment of the Independent Afghan Judicial Commission, and acting as an officer for the Emergency Loya Jirga Commission. She has also been integral to women's mobilization in reconstruction working for the Afghan Women Development Association as Director, the Afghan Women Judges Association as Director, UNIFEM Afghanistan as a Gender Justice Officer, and acting on the Afghan Constitution Commission in a unit for women in the election process. An accomplished and knowledgeable woman, she has attended and spoken at various international conferences including the "Women in Post-Conflict Situations" in Tokyo Japan, "Women and Gender Equality" in Paris, France, and "The Muslim Women in the World Conference," Berlin, Germany. Most recently, Basel has received her Master's in International Law from George Washington University." (Found at: http://www.mershon.ohio-state.edu/Events/05-06events/afghanwomen/afghanbios.htm)

An article written about Marzia Basel can be found at: http://www.entango.com/Clients/News/Articles/WashPost-EduDev.html

After our visit with Ms. Basel, we made way to our first lunch out on the town. After our initial day, all lunches would be enjoyed at restaurants in the city. Upon arriving at our destination, it became obvious that the first restaurant we would be eating at was owned by a relative of Davud, one of our drivers. We would come to find out that Davud's relatives were quite the business men and owned at least a few of the businesses around Chicken Street (a Kabul "strip" with restaurants and handicraft shops.) Our delegation was led inside and up a stairway to a pleasant, well decorated little place. We were given a room of our own and immediately waiters were at work pushing the numerous tables together to make one long table to accommodate us all.

This first lunch at a restaurant presented one of the first hurdle of traveling in a large group (particularly of Westerners) - were we going to eat individual meals or share "family" style? In my experience of eating among non-Westerners (in the United States and abroad,) it is often somewhat of an odd notion to order and eat individual meals, not to mention the challenge it poses to the servers when taking orders for sixteen people. With only a minor amount of displeasure from a couple delegation members, we concluded we would eat family style, which would be the case for the majority of our time in Kabul. In time, we all agreed on cucumber salads, rice (made in the delicious, traditional Afghan way - raisins and steamed peeled carrots,) kebab, and naan. It was at this point we learned that the Bird Flu Virus had made its way into Afghanistan and Afghans were advised against eating any chicken products. Many of the group still insisted that they wanted chicken kebab in spite of this and our Afghan friends at the table politely refused to eat any when it was passed their way. Fortunately, I have yet to hear of any of our delegation coming down with the Bird Flu Virus upon returning home. : )

Only one more visit was to be made after lunch that day. Our vans headed toward a neighborhood we had yet to see as we proceeded to visit Suraya Parleka, the founder of the All Afghan Women's Union. Like all of our visits, we were sat at a large table and served pastries and chai. We went around the table and introduced ourselves and it was at this point that I finally felt brave enough to introduce myself in Farsi. The two official languages spoken in Afghanistan are Dari and Pashtun. Dari is the local name used for the Persian language in Afghanistan. (Dari (also called Gabri or Yazdi) is the name used by Zoroastrians to refer to the Northwestern Iranian language they speak. It is also the name of the Persian language in classical Persian poetry.... wikipedia.org.) Though there are certain differences between Farsi taught in the university, as well as the Persian spoken by Iranians, I was able to understand and communicate a considerable amount. And as usual, it is always received with an immense amount of enthusiasm and appreciation upon trying.

Suraya didn't speak a significant amount of English so Najib translated for her. Her depth and seriousness reflected in her voice and gestures, however, as she spoke about the history of and her involvement with the organization, as well as stories from her own personal life. In 1965, Suraya was a student of Economics at the University of Kabul where she was actively involved with the Women's Democratic Association student group. At the time, the Constitution of Afghanistan enabled women to vote and work for Parliament, yet a law existed prohibiting Afghan women from traveling outside of Afghanistan, even with mahram (a male relative.) Suraya, along with several other women from the Association, lobbied at the Parliament for fifty days, becoming instrumental in the eradication of this law.

Because of her activism, Suraya and six other women were imprisoned for a year and a half in the late 1980's in which many of them experienced torture such as cigarette burns, electrical shocks and pulling out of nails. A regime change in 1991 led to their release and it was at that time that the All Afghan Women's Union was established, with Suraya elected as the director. The association began advocating for women's rights, working to establish day cares at work places and six-month leaves of absence for new mothers, as well as lobbying for new laws preventing men from taking a second wife. Civil war between several different Mujahideen groups began in 1992, however, making their work immensely difficult among such warfare. Women were targeted by some of the more fundamental groups and violence against women increased (often a tactic during times of war.)

Throughout civil war and the Taliban regime, Suraya remained in Afghanistan and continued her work with the All Afghan Women's Union, mainly in secret. During the Taliban regime, the organization helped establish thousands of secret home courses for girls. Suraya reflected upon how, oftentimes, the wives of Taliban, once hearing their husbands speak about making raids on certain houses they suspected were holding such classes, would secretly send letters to these women in order to warn them of the raids ahead of time.

On speaking about the current status of women in Afghanistan since the fall of the Taliban regime, Suraya feels that the new changes for women are more symbolic than they are reality, and the laws in the new constitution regarding women's rights aren't necessarily practical. She criticized the work of the newly established Ministry of Women's Affairs for inefficient use of governmental funding. At this point, Suraya and the All Afghan Womens Union aren't having to do their work in secret and include training women in craft making, job placement and literacy courses. However, Suraya still continues to be a target of harassment for her activism, yet she remains completely dedicated to her work.